Arts & Culture

The Blue Seas Saga

Some of the best rock bands of the 1970s recorded at Blue Seas Recording Studios, until it sank, under mysterious circumstances, into the harbor.

It’s not every day you see a guitar floating in the Inner Harbor.

But on Christmas Day 1977, a Martin D-28 guitar drifted past Pier 4, along with reels of audiotape, microphones, speaker monitors, a recording console, and a 1906 Steinway grand piano.

As the items scattered, an old barge lay almost fully submerged near its moorings at the pier, not far from where the Hard Rock Cafe stands today. As unlikely as it sounds, the musical equipment floated out of the barge, which had been converted into a high-end recording studio called Blue Seas.

In that pre-Rouse era, the studio/barge was one of the Harbor’s most notable tenants. Its upper deck was used as a stage for City Fair performances, and some of the most enduring and beloved rock albums of the 1970s were made at Blue Seas—Little Feat, Robert Palmer, Bonnie Raitt, and Emmylou Harris all recorded there, along with dozens of local bands.

All sorts of rumors and theories quickly surfaced in the wake of its demise. Some said drugs were involved. A few suggested it was the work of a disgruntled employee or some nefarious out-of-towner. Others even accused the owner, the bass player from The Lovin’ Spoonful, of sinking it to collect insurance money.

The Blue Seas saga, murky as the harbor water that engulfed it, eventually took its place in local music mythology. But the full story of its ascent and demise has never been told, until now.

The Blue Seas story begins in the early 1960s at, of all places, Baltimore Polytechnic Institute on Calvert Street and North Avenue. There, 15-year-old electronics whiz George Massenburg spent his days honing the science and math skills that would later prove invaluable to him as a Grammy-winning recording engineer and producer.

Obsessive about music and recording gear, Massenburg got an after-school job at local studio Recordings Incorporated on Cold Spring Lane. “A next-door neighbor introduced me to [the studio] around 1962,” says Massenburg. “It was really my first exposure to very high quality music recording.”

After graduating from Poly, Massenburg briefly studied electrical engineering at Johns Hopkins and began experimenting with parametric equalization, which allows engineers more precise control over the musical sounds they record. He left Hopkins to more fully develop the technology, working at International Telecom Incorporated (ITI), the firm that took over Recordings Incorporated in the late 1960s. By 1973, ITI had relocated to Hunt Valley and was on the brink of collapse, and Massenburg had left to work in Paris and Los Angeles.

Enter Steve Boone, former bass player for The Lovin’ Spoonful and co-writer of the ubiquitous 1960s hits “Summer In the City” and “You Didn’t Have to be so Nice.” An avid sailor, he had spent the three years since the breakup of the Spoonful living on a sailboat in the Virgin Islands. He returned to the U.S. to visit a friend, singer Trudy Morgal, who happened to be recording at ITI.

While visiting ITI, Boone was asked by studio management if he’d be interested in the facility. He had to stifle a laugh. “I returned to the States in no position to buy or lease anything,” says Boone, now bald and clean-shaven and currently living in North Carolina. But he also realized that ITI possessed Massenburg’s state-of-the-art equipment.

On a whim, he called the Spoonful’s manager, Bob Cavallo, and told him about the recording studio. “I asked if he could send me any business,” says Boone. “I was expecting to hear something like, ‘How will I get one of my stars to go to suburban Baltimore and record?’ But he knew of the facility and asked me if I had ever heard of Lowell George and his band Little Feat.”

At the time, the Los Angeles-based Little Feat was one of the most critically acclaimed rock bands in the country and seemed on the verge of making it big. But after the relative commercial failure of its first three albums, the band was also on the verge of breaking up. “It was a great hobby, but we weren’t making any money,” Lowell George told ZigZag magazine in 1975. “We really weren’t surviving. So I suggested to everybody that we try and find employment while we figure out a new hustle.”

Then, George got a call from Cavallo about the studio in Baltimore. “I dropped everything,” recalled George, “and said, ‘Yikes, that’s it!’”

His enthusiasm had a lot to do with the studio’s connection to Massenburg. George, who passed away in 1979, already knew Massenburg, as the two had worked on a few L.A. sessions together and had struck up a friendship. Massenburg was in Paris at the time, but with some prodding from the folks at Warner Brothers, he agreed to return to Baltimore to record Little Feat.

With those commitments in place, Boone was able to lease the Hunt Valley facility with money the record label paid for studio time. He rechristened it Blue Seas Recording Studios, because he loved to sail. He had no idea how prescient that name would be.

Upon arriving in Baltimore, the members of Little Feat had little trouble making themselves at home. George and his family rented a house in Cockeysville, just a short drive from the studio. Not long after, George’s wife Elizabeth gave birth to a daughter at GBMC. (Inara George is now a member of the indie group The Bird and the Bee.)

“It was an exciting adventure,” recalls Elizabeth. “Little Feat had been really in turmoil. Just getting away was great, because it was really touch and go at that point. Hollywood was getting to be not a very good influence, and so it was wonderful they all went to ‘the country.’ Everybody had a good time.”

Baltimore agreed with the band, personally and professionally. Guitarist Paul Barrere met his ex-wife Debbie, a Towson native, during the sessions, and keyboard player Bill Payne met his future wife and collaborator, Fran Tate, when she arrived at Blue Seas with her friend Emmylou Harris to provide backing vocals. Bonnie Raitt also came by and sang on the album.

That album, Feats Don’t Fail Me Now, is arguably the band’s finest. A unique mix of rock, blues, country, and New Orleans jazz, it includes bonafide classics such as “Rock & Roll Doctor” and “Oh, Atlanta,” and captures the band at the height of its powers. “Those guys were monsters,” says Boone. “Hearing them play together, it was obvious that it was an awesome band.”

Feats Don’t Fail Me Now received glowing reviews, eventually went gold, and was the band’s first album to reach the Billboard Top 200, where it peaked at number 36. Named one of the “100 Best Albums of All Time” by The Times of London in 1993, it was also cited by songwriter/tastemaker Elvis Costello as one of his “500 Albums You Need.”

After Feats was in the can, Little Feat remained in Baltimore to work with English singer Robert Palmer, who became Boone’s next high-profile client. George had played guitar on Palmer’s 1974 debut, Sneakin’ Sally Through the Alley, and the singer was keen on recording with Little Feat as his backing band. Fine, George said. But you have to come to Baltimore.

So Palmer’s next disc, Pressure Drop, was recorded at Blue Seas. “I remember thinking that this could be a waste of time and money,” says Steve Smith, who produced the album. “But [George] was adamant that it would work, and I went there trusting his instincts. And yes, it did work out. What we recorded [at Blue Seas] was fabulous.”

Although Palmer, who died of a heart attack in 2003, would become better known for 1980’s pop staples like “Addicted to Love” and “Simply Irresistible,” he made the charts with Pressure Drop, which included the funky gem “Work to Make It Work” and a cover of Little Feat’s “Trouble.” Looking back, Smith calls it “an unprecedented collaboration by a working band and a solo artist that has probably never worked better.”

Little Feat left Baltimore with renewed purpose, and Bill Payne later called his stay in the area “the best time in my life.”

Meanwhile, Blue Seas appeared to be flourishing. After producing a pair of acclaimed albums—a rare feat for a facility without a New York or Los Angeles address—the studio seemed poised for major success. But it didn’t happen, and the Blue Seas saga turned truly bizarre.

In early 1975, the Hunt Valley Business Community—which was owned by the venerable McCormick family—started eviction proceedings against ITI and Blue Seas. It was, according to Boone, due to a variety of issues, including rent owed from the period before he took over the operation. But Boone, who was still leasing the facility, says that was just part of the problem.

Blue Seas had become a meeting place for longhaired musicians, and their round-the-clock hours and rock-’n’-roll lifestyle hardly jibed with the buttoned-down, corporate aesthetic of its Hunt Valley home. Mattresses on the studio floor spawned rumors of orgies, although Blue Seas employees claimed they were only used for crashing after late-night sessions.

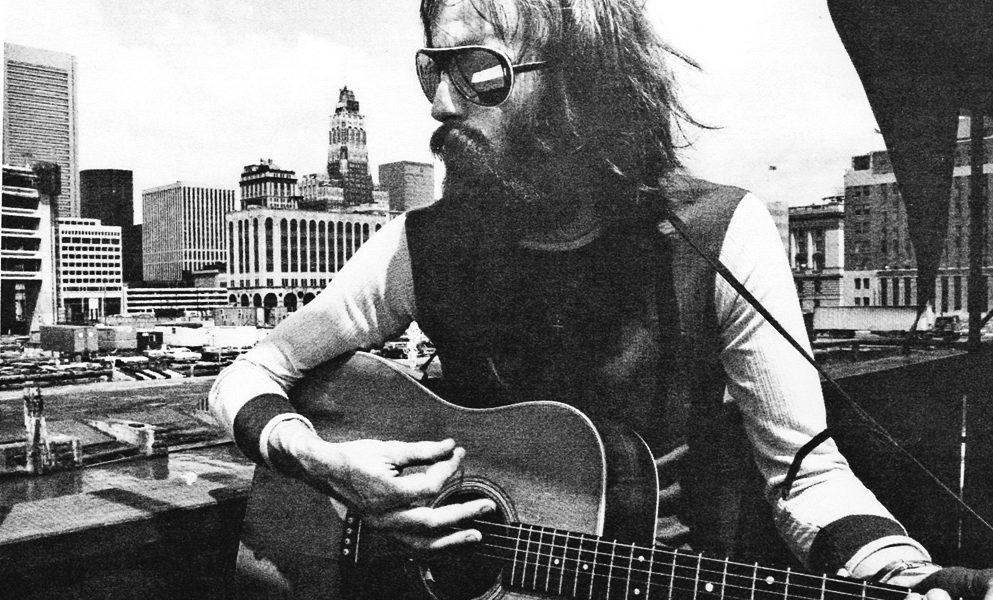

“I’m at my house and I get a phone call from my manager who says there’s a sheriff’s captain, some man named McCormick, and a bank officer from Maryland National Bank there threatening to evict us,” says Boone. “And so I get over there—and at the time I was a sight to see, 6-foot-4, 160 pounds, a beard down to my chest and long, long hair—and I walk into the studio and read them the riot act. It was like, ‘You people don’t know what you’re doing. You’re going to throw rock ’n’ roll out of Baltimore County. Baltimore will regret this day.’ And to his credit, [McCormick] stood there and took it.”

In January, the studio and its contents were put up for auction. There were to be two separate biddings, one for the entire studio and all of the equipment therein, and the second, an itemized auction for just the equipment. The higher total would determine whether the studio was sold as a lot or piece-by-piece.

From the outset, it was clear that the potential bidders were more interested in the high-end equipment—such as Massenburg’s state-of-the-art console—than in owning a studio outright. So when the bidding stalled at $17,000, the auctioneer asked if there were any other offers, and Boone, out of the blue, blurted out, “$18,000!”

“I didn’t have 18 cents on me,” he says.

Before the piece-by-piece auction began, Boone noticed “the McCormick guy” huddling with the auctioneer. After they spoke, the auctioneer banged his gavel and announced, “Ladies and gentlemen, the auction is over. Steve Boone, you’ve bought the entire studio complex.”

He then told a flabbergasted Boone that he had an hour to come up with at least 10 percent of the $18,000 price tag, and 24 hours to pay off the balance. So Boone started conducting his own sale, right then and there. With help from Massenburg, he sold an eight-track recorder and various other items to raise the money needed to buy the studio.

“What I heard, although I never confirmed it,” says Boone, “was that McCormick was so impressed with my impassioned speech the day I read him the riot act that he conferred with Maryland National Bank, who was the note holder, and said, ‘Look, can we do these guys a solid?’”

However benevolent the act, Boone knew it was made with the tacit understanding that Blue Seas was no longer welcome in Hunt Valley.

Ever the sailor, Boone decided to reinvent Blue Seas as a floating recording studio and leased a barge moored at Pier 4—where the Hard Rock Cafe is now located—at the Inner Harbor. When Boone informed his colleagues of the idea, most of them laughed in his face but acknowledged the fact that it was an intriguing concept.

Massenburg—whose recording console was the crown jewel of the studio and would be the most essential piece in making the idea work and prosper—was particularly dubious. He was among those who noted that noise from the water, the city, and the boat itself would make getting quality recordings practically impossible.

“That was kind of how the whole thing began,” says Boone, “with everybody going, ‘This is a foolish waste of money, but if you insist on it, we’ll help you.’”

City officials were supportive of the effort, as well. After all, there weren’t many businesses relocating to the harbor at that time. “We got a lot of cooperation,” says Boone. “Mayor William Donald Schaefer threw the key to the city to us. We were treated charmingly by the city and the business community. . . . Everybody was just super cool.”

The barge, which had been converted into a houseboat by its owner, local attorney John Armor, was big and beautiful. It was 105 feet long and 32 feet wide, with a hanging fireplace, a spiral staircase, hardwood floors, and oriental rugs. “The bedrooms and bathrooms were set up at each end,” says Guy Phillips, who was the studio engineer, “and we basically moved the recording studio into the living area.”

Picture windows down both sides of the barge were covered with red velvet cut from an old stage curtain. It looked great, but it was mostly “for soundproofing,” says engineer Victor Giordano. “It was awesome.”

“It was the most beautiful recording studio I’ve ever seen,” says Bill Mueller, who helped install Massenburg’s console. “It was a work of art.”

After working night and day for six months, the technical challenges were met—a shock-absorbing system was installed to eliminate much of the noise—and the studio opened for business. Lowell George frequented the facility, though Little Feat never returned; Earth, Wind & Fire bass player Verdine White was also a regular visitor to the barge, bringing various acts to town to record demos; and manager Bob Cavallo sent Blue Seas some work, as well.

Boone and his cohorts also made an effort to tap into the local music scene. The Blue Seas crew frequented two of the only downtown rock clubs at the time—The Marble Bar and No Fish Today—to recruit bands. As a result, recording sessions might begin at three o’clock in the morning and last past daybreak.

Unfortunately, the all-important numbers weren’t lining up. “We weren’t making a lot of money, but we were making a lot of music, I’ll tell you that,” says Boone. Compounding matters, some Blue Seas employees and hangers-on had developed nasty drug habits.

As 1977 came to a close, decisions about the studio were going to have to be made. Ultimately, however, the waters of the Chesapeake determined its fate.

On Christmas Day 1977, Boone was at his parents’ house on Long Island, winding down from a day of holiday revelry, when he received a frantic phone call from an employee. “The boat is sinking,” he was told. “Your guitar is floating out to sea.”

The vessel’s lone working bilge pump—designed to pump away the water that collected at the bottom of the ship—had malfunctioned, and the barge sank under the weight of the water that had seeped in.

Boone rushed back to Baltimore. When he arrived, fire trucks were still there trying to pump water out, and Blue Seas staffers were scrambling to salvage what they could. Phillips fished Boone’s beloved Martin guitar out of the harbor. “That Martin guitar today has a little chip in the sound hole where I hauled it out,” says Phillips. “It was floating, and I hauled it out with a boat hook.”

The studio’s extensive tape library, including valuable Lowell George demos and Lovin’ Spoonful outtakes, was destroyed. “Everything else that got lost was mechanical equipment and could be replaced,” says Boone, “but losing all of those tapes really hurt.”

The rumors started almost immediately. The state began an investigation, focusing on the possibility that the boat, housing a troubled business, had been scuttled for the insurance money. The myth that Boone and his cohorts “busted the boat out” remains to this day in some circles, although that’s exactly what it is—myth.

Boone has always maintained that there was no insurance money, and John Armor, now living in North Carolina, confirms that fact.

“Then, after the state’s attorney office realized there was no insurance,” says Boone, “they started to turn their attention elsewhere and apparently somebody in a bar either in Fells Point or up on Eutaw Street had been blabbing that they sunk the barge and that they had done it in an act of vengeance.”

It sounded plausible, considering the egos and drugs that run rampant in the music business. But, according to Boone, “That person got tracked down, the police were pretty darned aggressive about it, and it turned out it might have just been a drunk bragging.”

When asked if he suspects that foul play, of any type, was involved, Armor gives a succinct response: “No, not at all.”

The actual reason for the sinking was much more mundane. “[The barge] had a wooden hull,” explains Boone, “and so it had enormous seams between the gigantic planks, and they only caulked it to about a foot above the waterline. We had two bilge systems, and if either one of those systems went out, the barge became at risk because the waterline only had to get above a foot, and then the water would come in as though a hole had been punched in the boat.”

In the end, it was determined that Blue Seas had sunk due to faulty design and a lack of proper maintenance.

When asked what eventually happened to the barge, Armor says it was bought for salvage and towed to the Westport mud flats at the south fork of the Patapsco. For years, it could be seen from the Hanover Street Bridge.

The death of Blue Seas did not usher Boone out of town, though he was finished as a studio owner. Already immersed in a new business of renovating homes, he stayed in the Baltimore area for 10 more years until the cold winters prompted a move back to his boyhood home of Florida. Boone now lives in Wilmington, North Carolina—close to the water, naturally—and tours occasionally with a version of The Lovin’ Spoonful.

“The greatest time I’ve ever had in terms of living in a city,” Boone says of his days in Baltimore. “I’ve lived in Manhattan, L.A., South Florida, but to my mind there’s no comparison. I still think it’s the best city in America to live in.”

For his part, Massenburg, who went on to work with the likes of Linda Ronstadt, Bonnie Raitt, Mary Chapin-Carpenter, and The Dixie Chicks, and won a Grammy for Technical Achievement in 1998, looks back on the Blue Seas era as “a great time in my life. We all learned a lot and worked like crazy.”

Still, Massenburg doesn’t seem fazed that Blue Seas never really got its due. “If I mourned the loss of everything that I’ve seen disappear without a ripple,” he says, “I’d be mourning all the time.”