SPOILER ALERT!!!

Oh, how I wish I had the discipline to write about this film without spoilers, but I don’t. So only read the following review of Gone Girl if you’ve already seen the movie (or read the book). Just to be clear, there aren’t a few minor spoilers scattered about this review, the whole review is one giant spoiler. (But here is the short, nonspoilery version of my thoughts: I have some problems with the film, particularly its inherent misogyny and the near-ruinous plot twists of the final act, but it’s David Fincher, who’s a goddamned genius. Of course you should see it.)

As was the case with Gillian Flynn’s wildly popular novel, I wish Gone Girl, the movie, was actually about the things it’s sort of about.

It’s sort of about the idea of personality as a construct and the different masks we put on to the world and to ourselves.

It’s sort of about the unknowability of other people, even those we’re closest to.

It’s sort of about our 24 hour news cycle and our need to sensationalize, to create black and white heroes and villains out of tragic events.

It’s sort of about the difficulty, the near impossibility, of sustaining a marriage through the uncharted waters of life.

But it’s not really about those things because the character of Amy throws everything out of whack. How can a movie about a psychopath—and make no mistake, that’s what Amy is—be about anything except for that psychopath? She’s such an outlier, such an over-the-top villain—a cold-blooded murderer, a master schemer, and a seductress, who is quick to accuse men of murder and rape—all she can really represent is herself.

(This was why I mourned the fact that the “Cool Girl” speech—one of the most trenchant bits of gender insight I’ve ever encountered in a novel—came from a book that was ultimately pulpy (at best) and misogynist (at worst). (If you’re not familiar with the Cool Girl speech, it posits that men have a fantasy about a mythical cool girl—who eats chili dogs, looks hot in a bikini, and never complains when he comes home late—and that women are actually complicit in creating that myth.))

But I can’t mourn the film Gone Girl isn’t—I can only deal with the one it is. And, as directed by Fincher, it is, unsurprisingly, wickedly entertaining, a winking who-done-it with a brilliant sense of style and a pitch-black heart.

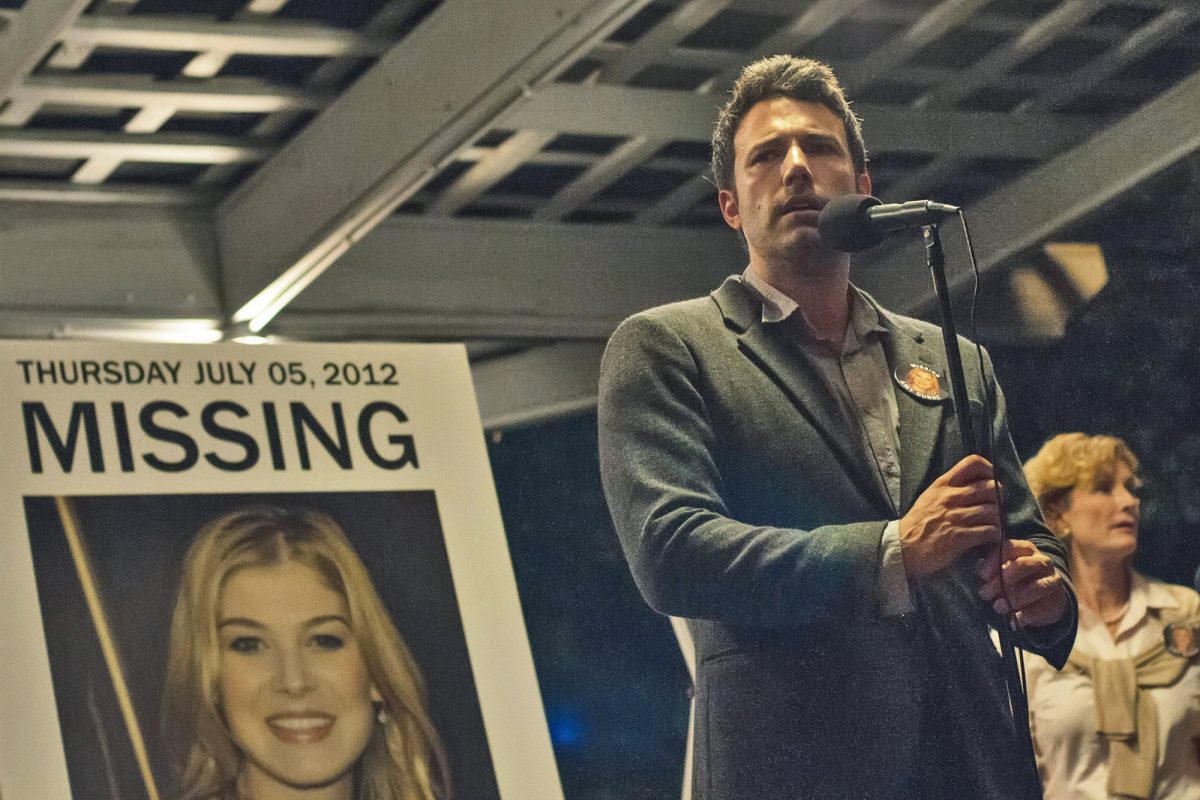

Out of a sense of duty, I’ll give you the plot: Writing teacher and bar owner Nick (Ben Affleck) comes home to discover that a glass table has been overturned and that his wife, Amy (Rosamund Pike)—the “Amazing Amy” of her parents’ aspirational series of children’s books—is missing. The cops come and immediately peg Nick as a suspect. Something is too neat about the crime scene, it seems staged. And Nick, who has carved out a persona for himself as a nice, polite guy, doesn’t quite know how to behave like a crazed-with-worry spouse. His tense smile makes him seem guilty. As the story moves forward, we find out that he is a little guilty—he and Amy were on the verge of a separation and he was having an affair with one of his students.

In the book, we get equal parts of Amy and Nick, something that gets lost a bit here. That kept us off balance, as our loyalties kept shifting between the two characters. Amy felt real to us—at least until she was revealed to be that ridiculous caricature. But in the movie, we’re virtually with Nick the whole time. Once we really get to spend any time with Amy, we already know she’s the bad guy. (It doesn’t help that our loyalties naturally lean toward Affleck over the little-known British actress Pike.) So part of the book’s fun—the whiplash of not knowing who to believe—is slightly diminished in the film.

On the other hand, Fincher improves on some aspects of the book, particularly the satirical ones. You can write about a rapacious, Nancy Grace-like news magazine host who follows the story of Amy’s disappearance with barely masked glee—but Missi Pyle’s hilarious performance really brings her to life. Ditto to the many scenes that show the insanity of the press following Nick around, chasing after him en masse, banging on his car like some sort of crazed mob.

The performances all range from good to great. With her long neck, alabaster skin, and refined nose, Pike looks very much like Amy the Ice Queen (and later, Amy the Murderer), but she never quite convinces as the “Cool Girl” Nick supposedly fell in love with. (She is great, however, in the scenes where Amy is hiding out, disdainful under her large sunglasses, in a sleazy motel.) Tyler Perry is hilarious—confident, cocksure, floating above the drama with an amused, seen-it-all smirk—as Nick’s shark of a lawyer. I also loved the work of Carrie Coon as Nick’s cynical but loving twin sister (their relationship is the closest thing the movie has to a beating heart).

But Affleck is nothing short of perfection as Nick. I knew the casting seemed spot on—Nick has to be a smart guy who can appear quite dim, the too-handsome guy with a blank canvas of a face and a shifty, uncertain smile. That practically is Affleck. But it’s unfair to say he’s just playing himself. The moment he shifts from patsy to aggressor during a TV interview—not incidentally, the moment Amy actually falls back in love with him—is a wonder to behold.

As for Fincher, this is his second film in a row (the last being The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo) where he’s tackled a novel that I feel is unworthy of his prodigious gifts. In both cases, his choices reveal an affinity toward the pulpy and perverse, and both films have serious women problems (I’m alluding to the fetishization of female violence in GWTDT). At some point, you have to wonder if Fincher, our most virtuoso director, just has lousy taste in source material.