Arts & Culture

Q&A with Marc Ferris

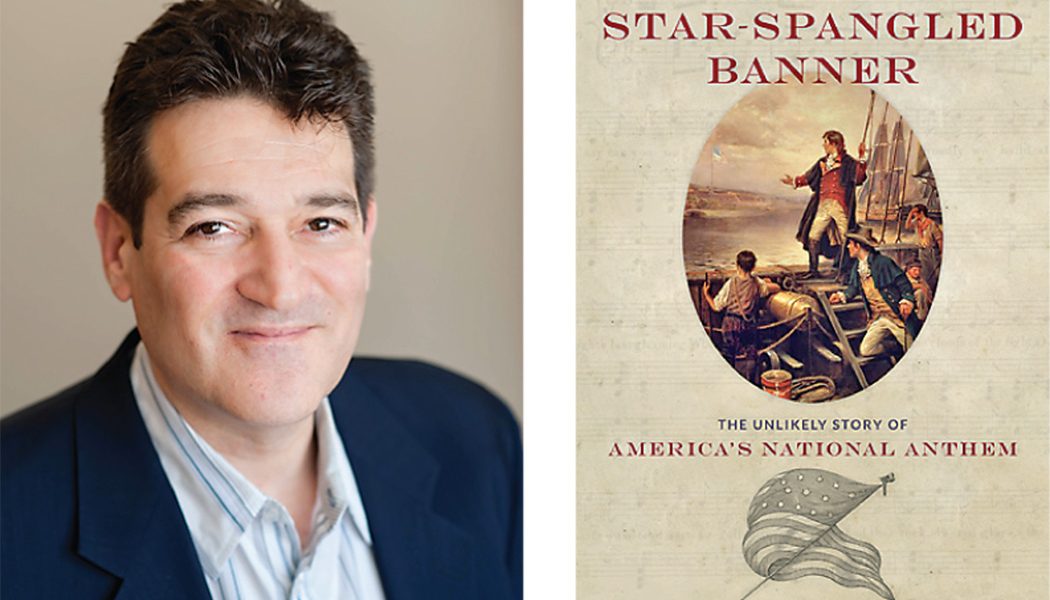

The author of Star-Spangled Banner: The Unlikely Story of America’s National Anthem talks about the anthem’s legacy and future.

What led to you tackling a book-length history of the anthem?

The idea flashed into my head in 1996 during a graduate history seminar at Stony Brook University. I love music and knew the song dated to 1814, so it had a significant heritage. Aware that its 200th anniversary would arrive in the not-too-distant future, I was pleasantly stunned to learn that very few books had been written about the most controversial song in American history.

Did you set out to write a biography of a song?

Indeed, it is a living, evolving entity that will never die. As I researched the song’s history that semester, I knew I was on to something big. The political uses of the song, the malleability of its meaning and the quirks of its trajectory intrigued me. Americans revere the song, but they don’t necessarily like it. I wanted to know how this composition became the official anthem, why it took 117 years to make it so and what made Congress act in 1931.

What is the greatest misconception about “The Star-Spangled Banner”?

In addition to the belief that the song is hard to sing, the notion that it glorifies war. Like a journalist, Francis Scott Key merely described what he saw on the night that England’s Navy bombarded Fort McHenry. Compared with The Marseillaise, the French anthem, which calls for patriots to water their fields with the enemy’s blood, Key’s verses are pretty tame. In the fourth verse, he also justified war (“then conquer we must”) only “when our cause it is just.”

I assume you visited Baltimore while researching the book. What did you think of the city and Baltimoreans’ relationship to the song?

Thanks to a Smithsonian Institution fellowship, I conducted considerable research at Fort McHenry, the Pratt Library and the Maryland Historical Society, where I discovered pivotal documents that enhanced the narrative. Baltimore is a main character in the book and local patriots helped make “The Star-Spangled Banner” the official national anthem. Most Americans dismiss the War of 1812, but the Battle of Baltimore represents a major David-vs.-Goliath victory.

What’s your favorite rendition? Why?

I am partial to Jose Feliciano’s singular, yet controversial version, performed almost a year before Jimi Hendrix’s incendiary rendition at Woodstock. Feliciano took heartfelt, creative liberties with the melody to forge one of the most distinctive performances in the song’s history. Honorable mention also goes to Marvin Gaye for originality and Doyle Lawson & Quicksilver’s a capella take for spine-tingling beauty.

There have, over the years, been rumblings about changing the anthem. Do you believe that will ever happen?

Never. Such talk is folly. Due in part to the inspiring circumstances of its creation and its focus on the flag, “The Star-Spangled Banner” became the de facto national anthem soon after it spread after the Battle of Baltimore. The major challengers over the years—including “Yankee Doodle”; “Hail, Columbia”; “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean”; “America the Beautiful” and “God Bless America”—are flawed. None of them have the same historical gravitas, or the edgy melody, of Key’s creation.