Just before lunchtime, as foot traffic outside of Lexington Market reaches its peak, regulars are raising their eyebrows—stopping to stare at a massive gold shipping container that has been positioned outside of the main entrance.

After conversing with Rachael London, who welcomes visitors in front of the container’s metallic-gold doors, they learn that the mysterious box is actually a room equipped with audio-visual technology that allows you to have face-to-face conversations with strangers from around the world.

“Some people are intimidated by it being such a small space” says London, a local artist who serves as the exhibit’s curator. “But once they see that they’re connecting to people who are energetic and welcoming, it’s not so scary.”

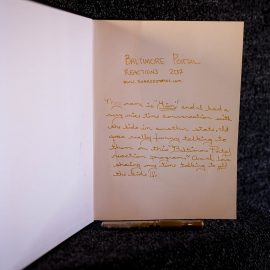

The immersive installation is called Portals, an initiative started by D.C.-based art collective Shared Studios. A giant screen inside the container streams live conversations with people visiting identical portals throughout the U.S., as well as countries like Mexico, Honduras, Rwanda, and Iraq. The goal, says London, is to create personal experiences that surpass boundaries, both geographic and otherwise.

“It kills stereotypes,” says Lewis Lee, a curator from Milwaukee who we connected with via the portal’s video chat technology on Monday. “We’re always stereotyping, but there’s nothing like getting the real information from the ground. It’s the ultimate tool to learn about different cultures and the way things work in different parts of the world.”

Specifically in Baltimore, the portal will be used as a mechanism to delve deeper into criminal justice issues. In addition to international calls, it will focus on connecting locals with strangers in cities like Los Angeles, Chicago, Atlanta, and Milwaukee to share their thoughts and suggestions regarding police reform. Curators help to moderate the conversation, starting participants with prompts such as “What would make today a good day for you?”

“Since we started a year ago, crime went down in our neighborhood by 21 percent,” says Lee, who mentions that the portal was place of reflection after last summer’s riots in Milwaukee, which bore strong similarities to the Baltimore Uprising. “The portal gave our community a sense of something to call their own—something to feel proud of. It brought the residents back, and gave us something to rally around.”

Organizers say that, after scouting multiple locations, they knew that Lexington Market would be an ideal home for the installation, which was brought to Baltimore by Downtown Partnership.

“Lexington Market is perfect because it’s bustling, and there’s no shortage of enthusiastic people,” says Michelle Moghtader, co-founder of Shared Studios. “There are two ways of doing outreach. You can either send an email, or plop a thing down in a crowded area and see who wants to come in and participate.”

Moghtader, an international journalist who launched the project in 2014, says that she has seen the portal evoke a number of impactful experiences, especially in the wake of President Trump’s recent immigration ban. She shares stories of Americans connecting with refugees in the Middle East, New Yorkers holding beat-boxing classes with people in Afghanistan, and an Iranian dancer performing for family in his home country.

“He said, ‘I feel like I’m breathing the same air as them,’” Moghtader recalls.

The installation will remain outside Lexington Market until Light City (March 31-April 8), when it will move to the intersection of Calvert and Water streets throughout the duration of the festival. Depending on funding, organizers hope to keep the portal downtown on a long-term basis.

“We’ve been overcoming trying times, and making a lot of progress because of the communication through the portals,” Lee says. “I’m scared to fly, so this is like my own virtual airplane.”